4 Rituals To Keep You Happy All The Time (Pandemic Edition)

.

The autopsies would show they had coughed so hard their abdominal muscles had been torn apart.

And some of the bodies had actually turned blue.

From The Great Influenza:

Cyanosis occurs when a victim turns blue because the lungs cannot transfer oxygen into the blood. In 1918 cyanosis was so extreme, turning some victims so dark—the entire body could take on color resembling that of the veins on one’s wrists—it sparked rumors that the disease was not influenza at all, but the Black Death.

At the time, clinicians had no idea what pathogen was capable of causing this.

Like any other rude guest, viruses don’t identify themselves. And frankly, in 1918, medicine was only just starting to hit its stride. It’s safe to say that before 1900, doctors were more likely to kill you than cure you.

From The Great Influenza:

…the 1889 edition of the Merck Manual of Medical Information recommended one hundred treatments for bronchitis, each one with its fervent believers, yet the current editor of the manual recognizes that “none of them worked.” The manual also recommended, among other things, champagne, strychnine, and nitroglycerin for seasickness.

We just hadn’t learned all that much yet. Humans had faced many challenges and many diseases but we just had not learned enough lessons from the past.

And that’s why they called Paul Lewis. He was brought in to solve this mystery. Lewis was the most unlikely of heroes. He was awkward. A military doctor who couldn’t even salute properly. But if he was subpar as a soldier, he was nothing less than a genius in the lab. His work on polio would lead to the vaccine that took that pathogen out of the headlines and into the history books.

But Lewis had his work cut out for him. Whatever this affliction was it was spreading rapaciously. Lewis was one of the greatest medical minds of his generation but he had no idea what this new disease could be. And then he realized the error they had all been making…

This pathogen wasn’t new at all. Paul realized it was mankind’s old enemy: influenza.

Humanity hadn’t learned.

The doctors were distracted by details, misled by its increased infectiousness. They’d lost so much time because they thought this was something altogether different. And that time they lost was so very precious.

From The Great Influenza:

Although the influenza pandemic stretched over two years, perhaps two-thirds of the deaths occurred in a period of twenty-four weeks, and more than half of those deaths occurred in even less time, from mid-September to early December 1918. Influenza killed more people in a year than the Black Death of the Middle Ages killed in a century; it killed more people in twenty-four weeks than AIDS has killed in twenty-four years.

The pandemic of 1918 killed more people than… well, anything. Ever. A low estimate pegs the deaths at 20 million (with a global population less than a third of today’s) but a more accurate number is somewhere between 50 to 100 million.

And you and I didn’t even hear much about the 1918 pandemic in high school.

And so here we are. Again. (sigh)

We humans have had it good for a while but then suddenly life’s like “you’re behind on your trauma payments” and whammo, we’re collectively standing around slack-jawed wondering if that Mayan calendar was right about the end of the world, just off by a few years.

No, this is not some political tirade or a lecture on the importance of epidemiology. Actually, this is about you and me and your life and my life and all of our lives in this pandemic.

And what we need to learn.

So what have we learned?

Hundreds of thousands of people have died. Months of quarantine lockdown. Doesn’t take AP Math to figure out that with something this big we should each come away with a personal lesson or two, right?

This will likely be the most historically important thing we live through — and it is more than humbling that you can state that with zero exaggeration or irony.

“Never let a crisis go to waste” is the old saying. I don’t mean that in the cynical, political way. I mean it in a life lessons kinda way. If you’ve been waiting for a “sign” to make some changes in your life, to make some decisions about who you are or how you live or what’s important to you, well, this is the time, Bubba.

Hello, this is the front desk. You requested a wake-up call.

How has the pandemic and quarantine impacted you?

What have you learned?

Who do you want to be going forward?

We’re gonna get through this together, you and me. Don’t worry, I brought some sandwiches. Oh, and some good science, as opposed to the fan fiction that passes for research on much of the internet.

We’re gonna figure out what we need to learn from this Matryoshka doll of calamities we’ve been living through. Time to generate some life lessons. Something to help guide us moving forward and maybe even something to bore the grandkids with one day.

Pull up a chair; we’re gonna break it down. Comfy? Good.

Let’s get to it…

“I learned a lesson about gratitude…”

Feeling gratitude during a pandemic might seem downright obscene. We’ve all experienced some Hall-of-Fame-level challenging things recently. (Here in Los Angeles my SoCal life has become “my so-called life.”)

But we’re still here. We’re alive. Gratitude is all about perspective. After a car accident you can be angry your Dodge Dart was totaled or you can choose to be thrilled you’re still alive. Up to you, chief.

“You don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone.” Yeah, it’s a cliché but it’s also some 8th Degree Black Belt psychology right there. This morning you read the 600th article about ICU respirators — instead of being on one.

Psychology has validated what Grandmom told us about happiness: count your blessings.

Think about how much epic heinous crap has occurred historically — truly horrible things like World Wars – and then think about how complacent we all were just a few months ago. We’ve spent three decades whining that the internet was slow and so now life is like “I’ll give you something to cry about…”

We took so many lovely things for granted.

Now that the world is reopening, how good does it feel to do some of the stuff you were deprived of during lockdown? In my interview with Harvard professor Mike Norton, he explained that taking a break from something you love and “making it a treat” can boost appreciation and happiness.

We just did a global happiness experiment and didn’t even realize it. Any time bad things happen but they don’t happen to you directly, there’s a reason to feel grateful. (Let me suggest that our not-dead status is a good place to start.)

Your Blessing Manager down in the accounting department hasn’t been doing her job. Start counting. Yes, having good stuff fall from the sky is nice but a much bigger part of happiness is where you choose to put your attention.

So what lesson did you learn about gratitude? What do you appreciate more now that you’ve been living through a pandemic and dealt with quarantine? What are you going to cherish a bit more now that it can’t be taken for granted?

Finish this sentence: “I realized I am so lucky to have…”

And now take a second to smile.

(To learn the most fun way to make your life awesome during the pandemic, click here.)

Okay, lesson number two is a cousin to gratitude but it’s still distinct and it’s something you’re going to want to do deliberately a lot more often…

“I learned a lesson about savoring…”

If gratitude is reflecting on the good things in life, savoring is appreciating those good things in the moment.

Now that the Earth is having an anaphylactic reaction to mankind and we’ve all been on a carousel of nightmarish deprivation, what are we going to deliberately pause and enjoy because we can’t take it for granted anymore?

Again, it’s about attention. We often think that it’s the world that makes us happy but it’s really how we respond to the world.

We don’t need more good stuff in order to be happy. Plenty of people all over the planet have far less than we do and smile every day. It’s about taking a second to really savor what’s already here.

Focusing on the positive and appreciating those things leads to a measurable happiness boost in less than a week.

Via Rapt: Attention and the Focused Life:

One group was told to focus on all the upbeat things they could find— sunshine, flowers, smiling pedestrians. Another was to look for negative stuff— graffiti, litter, frowning faces. The third group was instructed to walk just for the exercise. At the end of the week, when the walkers’ well-being was tested again, those who had deliberately targeted positive cues were happier than before the experiment. The negatively focused subjects were less happy, and the just plain exercisers scored in between. The point, says Bryant, is that “you see what you look for. And you can train yourself to attend to the joy out there waiting to be had, instead of passively waiting for it to come to you.”

(To learn more about how savoring can make you happier, click here.)

Next lesson should be obvious but, sadly, it’s probably not that obvious.

Welcome to 2020. There are invisible microscopic thingys in the air that can kill us.

Done taking your health for granted now?

“I learned a lesson about my health…”

For many of us it takes nothing less than a black ops extraordinary rendition to get our butts to the gym. Those days are over. Do it for vanity or do it for sanity but health is important and proper eating and exercise should seem a lot less optional.

You don’t need to be a health freak or a gym nut but most of us do not take care of our bodies.

From The Body:

Only about 20 percent of people manage even a moderate level of regular activity. Many get almost none at all. Today the average American walks only about a third of a mile a day—and that’s walking of all types, including around the house and workplace.

Some will say it’s not safe to go back to gyms yet and I’m not going to argue the details. But for 99% of our existence, humans didn’t spend a lot of time on Pilates machines anyway. However, they did move more. A lot more. And it turns out that’s what’s really important.

In the early 20th century people thought heart disease was mostly due to aging and stress. But Jeremy Morris, a doctor at Britain’s Medical Research Council, thought it was actually related to activity levels. After World War 2 there wasn’t a lot of money for research so he did a cheap natural experiment.

Each double-decker bus in London had two employees: a driver (who hardly moved all day) and a conductor (who barely got a chance to sit down.) Morris studied 35,000 pairs of them for two years. Guess what he found?

Controlling for other variables, drivers were twice as likely to have a heart attack as a conductor.

Lesson: we need to move more. Sitting on your butt all day is as genius an idea as sucking on downed electrical cables. And you don’t have to do a crazy amount of exercise to get substantial benefits.

From The Body:

Going for regular walks reduces the risk of heart attack or stroke by 31 percent. An analysis of 655,000 people in 2012 found that being active for just eleven minutes a day after the age of forty yielded 1.8 years of added life expectancy. Being active for an hour or more a day improved life expectancy by 4.2 years.

The pandemic is offering us all the chance to hit the reset button and make some positive changes in regard to our health — above and beyond washing our hands.

(To learn more about how to motivate yourself to exercise, click here.)

And, sadly, what has been great for our not-getting-COVID health has taken a significant toll on our emotional health. Yes, I mean the practice of “social distancing.” There’s another big lesson here…

“I learned a lesson about my relationships…”

Not since high school has an authority figure mandated that I cannot go out and see my friends. I live alone and during quarantine I have watched my social skills steadily decay until I regressed to some sort of “feral nerd” status. (Upside is there sure hasn’t been much FOMO.)

The research says that in terms of happiness, having a good social life is worth about $131,232 a year. So as far as smiles go, quarantine cost us a lot more than we ever imagined.

But, again, there’s an upside to this. Think about your personal relationship lesson. Who did you miss the most? And what are you going to do about it going forward?

When I spoke with Stanford professor Jennifer Aaker she said we often make a mistake in planning our lives. Even when we know what and who brings us joy, we don’t dedicate enough time to those projects and people:

…if you ask people to list the projects that energize (vs. deplete) them, and what people energize (vs. deplete them), and then monitor how they actually spend their time, you find a large percentage know what projects and people energize them, but do not in fact spend much time on those projects and with those people.

The solution? The good ol’ calendar. You now know who matters to you and who you need to see more often to be happy. Schedule something with them. Here’s Jennifer:

When you put something on a calendar, you’re more likely to actually do that activity – partly because you’re less likely to have to make an active decision whether you should do it – because it’s already on your calendar.

And please don’t hold your feelings back when you see your friends again. We’ve all been scared, locked up and deprived. Tell them you’ve missed them. Tell them you love them. You’ve got a globally recognized excuse for being all mushy.

(To learn the two-word morning ritual that will make you happy all day, click here.)

Okay, we’ve “learned our lesson.” Let’s round it all up — and find out how I just mischievously tricked you…

Sum Up

Here are 4 rituals to keep you happy all the time:

- Learn a lesson about gratitude: Forget your Dodge Dart. Be happy that it is wrapped around a telephone pole and you are not.

- Learn a lesson about savoring: Wanting more good stuff all the time is a trap. Take a moment to deliberately appreciate what you have in the moment.

- Learn a lesson about health: Be a conductor, not a driver.

- Learn a lesson about relationships: Who did you miss? Schedule something with them right now before you get distracted and your brain powerwashes everything you just learned out of your head.

So what have we learned? Maybe you still don’t have a great answer. That’s okay. I’ll bet you’re already a teensy bit happier now regardless. How do I know? Because I tricked you…

Another method to increase happiness and gratitude is merely taking the time to reflect on what you learned from tragedy. Which you just did above. Even if the exercises were fruitless, by taking the time to think about it the research says you should now be a bit happier than before you started. Nyah-nyah.

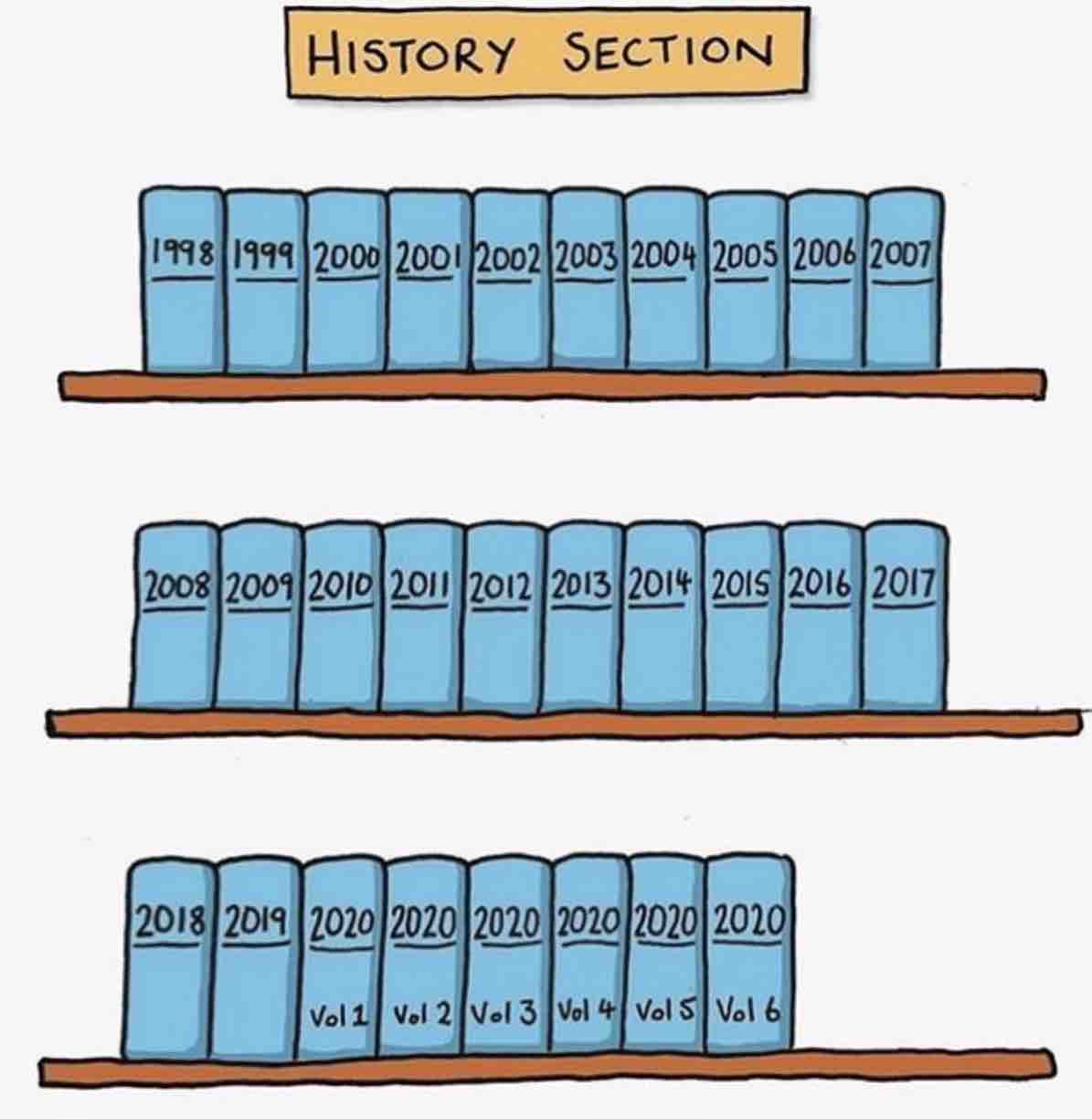

2020 has not been kind thus far. We’ve all had just about enough “character building” for one year… but the year is not over. While the scientists nobly continue to play epidemiological whac-a-mole we must stay the course and keep our chins up.

Unfortunately, many have learned how to die with this virus. Now we must learn how to live with it. At least for the near future. But if we keep learning and growing, we’ll make it through.

In 1918, they clearly hadn’t learned enough from prior epidemics to quickly identify our old nemesis influenza. And you and I didn’t learn much about 1918 because it’s not talked about much in schools. But we can choose to start learning more about ourselves from now on.

And, truth is, humans are pretty good at learning things to improve our lives if we take the time.

Looking at the data, on average, pretty much every animal gets 800 million heartbeats. It’s surprisingly consistent. The exception?

Humans. Yeah. Us. You and me.

For most of history we were just like every other species and only got about 800 million thump-thumps. We hit that number by age 25 and many of us only lived to age 25. But over the last 12 generations or so we got ourselves another 50 years and another 1.6 billion heartbeats.

We learned. Humans have big brains and sometimes we even use them. We used them to understand things better, to change the world and change our lives.

So I ask again: What did you learn?

There will always be tragedy. But don’t ignore its lessons.

Metaphorically — and literally — those lessons make our hearts stronger.

Join over 345,000 readers. Get a free weekly update via email here.

Related posts:

New Neuroscience Reveals 4 Rituals That Will Make You Happy

New Harvard Research Reveals A Fun Way To Be More Successful

How To Get People To Like You: 7 Ways From An FBI Behavior Expert