This Is The Most Fun Way To Make Your Life Awesome

.

***

Before we commence with the festivities, I wanted to thank everyone for helping my first book become a Wall Street Journal bestseller. To check it out, click here.

***

“The internet is making smart people smarter and dumb people dumber.”

That’s writer Kevin Drum. On the surface it would seem that the internet should be making us all smarter, right?. The world’s information is just a Google search away.

But what happened when Carnegie Mellon researchers studied the effects of in-school broadband access?

From Curious:

They found that the schools that allowed their pupils higher levels of broadband use achieved worse grades than those that didn’t.

Okay, but kids are gonna screw around, right? What about adults? They can sign up for awesome stuff like online classes to learn about anything and adults are clearly more motivated to…

Well, no, not really.

From Curious:

According to the New York Times, “Less than 10 per cent of MOOC students finish the courses they sign up for on their own.”

Turns out it’s not about mere access to information. You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it think. In the end, it’s about the person and the traits of that person to determine whether they use something and how they use it. And you and I are really talking about one trait in particular:

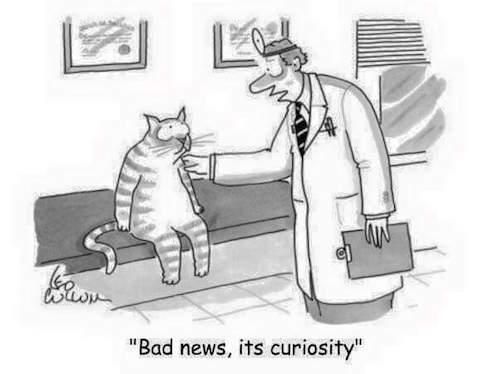

Curiosity.

We don’t take that word very seriously. In fact, the expression “just curious” is used to imply low stakes, that something is not a big deal. Heck, “learning experience” is a euphemism for the painful moments in life.

All of this is downright terrible because curiosity is an amazing thing – and these days it’s more valuable than ever, especially since the advent of the internet. I can wax poetic about the joy of learning but it turns out the benefits of being curious go far deeper: improving your finances, your health and even your relationships. The research shows curiosity, quite simply, leads to a better, richer life with a much higher threadcount.

Problem is, curiosity may also be more rare than ever. So how about you and I make sure that we’re the smart people that the internet is making smarter – instead of the opposite?

We’re gonna get some help from a few solid books on the subject: Ian Leslie’s wonderful Curious, Mario Livio’s Why? What Makes Us Curious and Perry Zurn’s Curiosity Studies.

Curious to learn more? (If so, we’re already off to a good start.)

Let’s get to it…

Curiouser And Curiouser

The first sentence of Aristotle’s Metaphysics is “All men by nature desire to know.”

But what is curiosity?

From Why? What Makes Us Curious:

…epistemic curiosity appears to aim at two goals: to act as a motivator for us to understand the limits of potential choices and, more important, to maximize knowledge and competence.

From an evolutionary perspective, curiosity helps us get ahead of the game, to learn more about our environment so we can cheat on the test of life. Your brain is never exactly sure what info it might need in the future so it spreads its cognitive bets beyond the immediate.

Caltech neuroscientists stuffed people in an fMRI scanner and read them trivia questions. What part of their brains lit up? The caudate nucleus — which is associated with not just learning but also romantic love. Your brain finds curiosity intrinsically rewarding at the most fundamental level. And it’s not just pleasurable, it’s practical. When curiosity is piqued, people retained information better 24 hours later.

Now that’s all fine and dandy but does it have any concrete, real-world benefits? You better believe it. The curiosity of babies predicted grades in school more than a decade later.

From Curious:

They found that the ones doing best at school aged fourteen were the ones who had been the most energetically exploratory babies.

In fact, curiosity contributes to academic success as much as being super-organized.

From Curious:

Sophie von Stumm, a lecturer in psychology at Goldsmiths University, led a review of existing research on individual differences in academic performance, gathering data from 200 studies, covering a total of about fifty thousand students… von Stumm and her collaborators found that curiosity had roughly as big an effect on performance as conscientiousness.

Even if you’re well-past your school years, it’s still insanely valuable. A 2013 study of the elderly found those who were interested in new ideas and did cognitively demanding stuff stayed sharper as the years went by.

From Curious:

…the subjects who made a lifelong habit of a lot of reading and writing slowed their rate of mental decline by a third compared to those who did only an average amount of those things… People who rarely read or wrote experienced a decline that was a staggering 48 percent faster compared to the average participants.

Curiosity even improves your relationships. Couples that seek out new, interesting stuff to do together were the ones that stayed in love.

From Curious:

The couples that engaged in the “novel and arousing” activities were significantly more likely to express satisfaction in their relationship afterward and to feel romantically about the other.

(To learn more about how you can lead a successful life, check out my bestselling book here.)

And the bad news? Curiosity starts to wane as early as age four. If you want to keep that amazing trait past your larval stage, you’re gonna have to work for it. Otherwise, your brain is going to stop looking for new stuff and just go back to updating its MySpace page.

So how do we stay curious and get all those wonderful benefits?

1) Build The Storehouse

Curiosity is paradoxical. Turns out we’re not curious because we lack knowledge, knowledge actually increases curiosity.

There’s a Goldilocks balance here. Most people aren’t curious about things they know nothing about. We say “Hmmm” when we know a little and feel we’d benefit from knowing more.

From Curious:

Loewenstein pointed out that a person who knows the capitals of three out of fifty American states is likely to think of herself as knowing something (“I know three state capitals”). But a person who has learned the names of forty-seven state capitals is likely to think of herself as not knowing three state capitals. She’s likely to want to learn those last three and will make an effort to do so.

Curiosity compounds with knowledge. The more we know, the more “hooks” we have to hang new information on. We’re more able to make connections and integrate ideas. When we don’t know anything about a subject, we become disinterested and forget.

So, ironically, the best way to become curious about learning things is to keep learning things. More hooks, more connections, until almost everything is related to something you already know.

This isn’t just “learning for learning’s sake.” Building your storehouse of knowledge unlocks a new world. Suddenly the flat, gray areas of life are in 3-D because you’re more connected to everything you experience.

From Curious:

It means you get more out of a trip to the theater or a museum or from a novel, a poem, or a history book. It means you can glance at the first few paragraphs of a story in the Economist, grasp its essentials, and discuss them later. It means you can engage with the person next to you at lunch on a broader range of topics, contribute meaningfully to more meetings, be more skeptical of dubious claims, and ask better questions of everyone you encounter. Whoever you are and whatever start you get in life, knowing stuff makes the world more abundant with possibility and gleams of light more likely to illuminate the darkness.

(To learn the 4 harsh truths that will make you a better person, click here.)

So how do we get started? And is this going to be a lot of work? No. And even if it does require some effort, if you do it right, you won’t mind at all…

2) Start Where You Are

No, you don’t need to start reading things that don’t interest you. As we established, curiosity blossoms in areas where you already have some knowledge. So just dig a little deeper into subjects that already fascinate you. Building curiosity is a labor of love, not a labor of labor.

What beguiles you? What makes your brain do “jazz hands”? No judgments. Do you like reading about celebrities? Fine. Go check out their Wikipedia page. And then start link hopping.

Take the next step. Broaden a bit. Curiosity will branch as you learn, building bridges to new topics you never thought you’d be interested in. How much did you care about epidemiology and viruses a few years ago?

(To learn the two-word morning ritual that will make you happy all day, click here.)

But it’s not all about you, alone, doing Wikipedia searches. It’s also about how you approach everyday life…

3) Surprise Yourself And Others

We tend to get into ruts. You can become so apathetic you’d make a great DMV employee. So make an effort to notice what surprises you every day. Instead of letting it drift away, whip out your phone and pursue it a bit.

From Why? What Makes Us Curious:

…getting genuinely interested, a few times a week, in at least one of the many events, people, facts, or phenomena we encounter on a daily basis. This could include reading about what determines the path of forked lightning in a rainstorm, inquiring about the hobby of a coworker, examining a new application for the smartphone, following up on a particular tweet, or trying to understand the behavior of the stock market.

When something piques your interest, let yourself go down the rabbit hole. This is how people find new passions. They don’t let interestingness slip away. And when you pursue interestingness, you become a more unique person with many facets and more depth.

Keep this up and if you’re not careful, you might become someone that people find fascinating.

(To learn how to stop being lazy and get more done, click here.)

Okay, but what about topics that are just downright dull? Some subjects possess levels of boredom that make Dante’s Inferno look like Chuck E. Cheese. Totally unspirational. What then?

4) Go Deeper

It used to be easier to get curious because it was harder. No, that’s not a typo.

I’ll bet that confusing statement made you curious. Why? Because it’s a challenge. Researchers call it “productive frustration.” It opened a gap in your knowledge that made you say, “Huh? Why?” It’s the same trick clickbait headlines use.

When something is a bit harder to grasp, we actually learn better. If we learn something quickly, we forget it quickly. This is why when you cram for a test you don’t retain the information. We need a bit of challenge to get us motivated and to make our lazy brains bring their A-game.

But these days the internet makes getting answers quick and easy. In the past you had to really dig, and that digging made the facts stick. More effort means more retention. More retention means more knowledge. More knowledge means more hooks, connections and curiosity.

So dig a little deeper. Don’t outsource to your friend Siri. Buy a book about the subject. Watch a video. Do something nobody has ever done in the history of the universe – go to the second page of a Google search.

Roll up your sleeves a bit and don’t just get the immediate answer, challenge yourself to really understand the topic a bit. There’s a lot of intellectually ravishing ideas a few inches beneath the surface if you look.

Famed physicist Richard Feynman said, “I don’t know anything, but I do know that everything is interesting if you go into it deeply enough.”

(To learn the best time to do anything, click here.)

But is increasing curiosity a fundamentally solitary endeavor? Not by a long shot…

5) Ask Questions

Psychologist Michelle Chouinard found that between the ages of 2 and 5 children ask more than 40,000 questions. And this works. Kids learn, and they learn fast. We’d be better off if we did the same. (Okay, maybe not 40,000-questions-level-of-same, but you get the point.)

Want to make more money? Want to be a better negotiator? Well, curiosity can be the difference between driving a new car and living in it. The best negotiators are relentlessly curious. And their Flux Capacitor levels of negotiating power often come from the simple question “Why?”

Knowing why someone wants something allows you to come up with creative solutions for how you can both get what you want.

From Curious:

…if each party accepts the other’s negotiating position on its own terms, then the most likely result is deadlock. The key, he says, is to ask what lies beneath the demand. “The fundamental question,” according to Powell, “isn’t ‘what,’ it’s ‘why.’” If the parties negotiate on their preagreed positions, the negotiation becomes a trade-off in which one side loses while another one gains. “But,” Powell said, “if you ask what people’s underlying interests are—what do they need—then you’re more likely to find an imaginative solution.”

But life isn’t all about money. Asking questions of those you love is one of the kindest and most generous things you can do. And the knowledge you gain improves your relationship. This is “empathic curiosity.”

From Curious:

…empathic curiosity: curiosity about the thoughts and feelings of other people… You practice empathic curiosity when you genuinely try to put yourself in the shoes—and the mind—of the person you’re talking to, to see things from their perspective. …curiosity is a deeply social quality.

What is the basis of love? Well, that Casanova guy (who might know a thing or two about the subject) felt it was actually curiosity:

The woman who showing little succeeds in making a man want to see more, has accomplished three-fourths of the task of making him fall in love with her; for is love anything else than a kind of curiosity?

Ask the people you love more questions about themselves. It doesn’t tell them you care; it shows them you care.

(To learn the 4 things the most organized people do every day, click here.)

Okay, we’ve learned a lot. Let’s round it all up – and learn how curiosity can lead to a better life…

Sum Up

Here’s how to be more curious:

- Build Your Storehouse: Curiosity leads to knowledge, but knowledge also leads to curiosity.

- Start where you are: Learning about Hugh Jackman can make you curious about Wolverine and Wolverine can make you curious about healing and healing can make you curious about stem cell research.

- Surprise yourself and others: When companies start secret projects it’s common that everyone involved has to sign an NDA. The development of the original iPhone was so secret that people had to sign an NDA in order to sign the iPhone’s NDA… Hmm, so how do NDA’s work?

- Go deeper: Did you know that telling something to a priest is a form of NDA and is protected under US law? (You have to dig a little more to learn that one.)

- Ask questions: So what made you curious enough to read this far? Have you always been a curious person?

I grew up watching Jeopardy with my father. To this day he’ll text me the Final Jeopardy question to see if I know the answer. And just like Batman’s entire career was based on childhood PTSD, in a much more positive way, the curiosity engendered by watching all those episodes with my dad led me to be a very curious person. I read endlessly, started a blog and collected enough books to turn my living room into 300 square feet of hoarder paradise.

Those early years of questioning developed into an all-consuming curiosity. I feared I might enter a Wikipedia rabbit hole from which I would never return, never being focused enough to actually get my act together…

But all those odd facts and information ended up coalescing into a book I wrote. And then one night in April of 2021, my book was the answer to a question on Jeopardy.

I can’t imagine anything that could have made my father more proud.

I still want to learn everything about the world. And I will fail at that. But it will be worth it. It’s an addiction I don’t want rehab for. And it’s a habit I would recommend to you as well.

Curiosity is regarded as a childlike quality, but one that ironically leads to a much richer life as an adult. The world shrinks or grows as a function of your curiosity. It draws more richness and depth from every moment and allows us to appreciate things we never would have noticed otherwise.

When we stop being curious, we stop caring. And when we stop caring we begin to die inside.

From Curiosity:

There is only one way out of the madness, and that is to let our curiosity take us by the hand and lead us. Follow your curiosity, therefore. It will encourage you to take risks, to be creative, sociable, and entertaining. It will ask you to think about how you should live.

You have dreams. What if you could learn the secrets to how to make them come true?

The answers are out there. Are you looking for them?

I’m “just curious.”

Join over 345,000 readers. Get a free weekly update via email here.

Related posts:

New Neuroscience Reveals 4 Rituals That Will Make You Happy

New Harvard Research Reveals A Fun Way To Be More Successful

How To Get People To Like You: 7 Ways From An FBI Behavior Expert