Group flow: How can teams experience “flow” together?

.

Group flow. It almost seems like a contradiction. Flow is always described as something individuals experience.

I’ve posted research into what top creative companies and creative teams do right but can groups actually experience “Flow“?

Flow is the mental state of operation in which a person performing an activity is fully immersed in a feeling of energized focus, full involvement, and enjoyment in the process of the activity… The hallmark of flow is a feeling of spontaneous joy, even rapture, while performing a task although flow is also described… as a deep focus on nothing but the activity – not even oneself or one’s emotions.

Keith Sawyer studied under Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (the researcher who created the idea of Flow) and studying jazz ensembles and improv groups as well as business professionals he realized that teams experiencing group flow were actually the best performers.

Via Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration:

I began to explore these question by studying jazz ensembles. I was a jazz pianist throughout high school and college, and I’ve often sat in with professional groups. Basing my research on Csikszentmihalyi’s seminal work, I discovered that, sure enough, improvising groups attain a collective state of mind that I call group flow. Group flow is a peak experience, a group performing at its top level of ability. In a study of over three hundred professionals at three companies— a strategy consulting firm, a government agency, and a petrochemical company— Rob Cross and Andrew Parker discovered that the people who participated in group flow were the highest performers.

What’s needed to create group flow?

Highlights from Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration:

1. The Group’s Goal

One study of more than five hundred professionals and managers in thirty companies found that unclear objectives became the biggest barrier to effective team performance. Jazz and improv groups are at the other extreme. The only goal is intrinsic to the performance itself— to perform well and to entertain the audience. This is problem-finding creativity because the group members have to “find” and define the problem as they’re solving it. At first, this might seem very different from everyday business contexts. But many of the most radical innovations occur when the question or goal isn’t known in advance.

2. Close Listening

Group flow is more likely to emerge when everyone is fully engaged— what improvisers call “deep listening,” in which members of the group don’t plan ahead what they’re going to say, but their statements are genuinely unplanned responses to what they hear. Innovation is blocked when one (or more) of the participants already has a preconceived idea of how to reach the goal; improvisers frown on this practice, pejoratively calling it “writing the script in your head.”

3. Complete Concentration

In group flow, the group is focused on the natural progress emerging from members’ work, not on meeting a deadline set by management. Flow is more likely to occur when attention is centered on the task. Small annoyances aren’t noticed, and the external rewards that may or may not await at the end of the task are forgotten. A strict deadline is certainly a challenge, but not the right kind of challenge; the challenges that inspire flow are those that are intrinsic to the task itself. Group flow is more likely when a group can draw a boundary, however temporary or virtual, between the group’s activity and everything else. Companies should identify a special location for group flow, or engage in a brief rehearsal or warm-up period that demarcates the shift to performance.

4. Being in Control

Group flow increases when people feel autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Many studies have found that team autonomy is the top predictor of team performance. But in group flow, unlike solo flow, control results in a paradox because participants must feel in control, yet at the same time they must remain flexible, listen closely, and always be willing to defer to the emergent flow of the group. The most innovative teams are the ones that can manage that paradox.

5. Blending Egos

In group flow, each person’s idea builds on those just contributed by his or her colleagues. The improvisation appears to be guided by an invisible hand toward a peak, but small ideas build and an innovation emerges. In discussing a colleague who often participated in groups in flow, one executive had this to say: “He is animated and engaged with you. He is also listening and reacting to what you are saying with undivided attention.”

6. Equal Participation

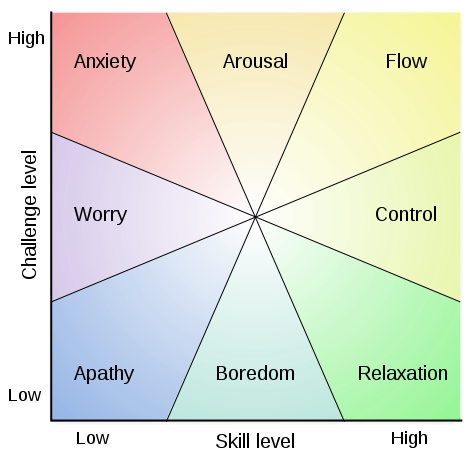

Group flow is more likely to occur when all participants play an equal role in the collective creation of the final performance. Group flow is blocked if anyone’s skill level is below that of the rest of the group’s members; all must have comparable skill levels. This is why professional athletes don’t enjoy playing with amateurs; group flow can’t emerge because the professionals will be bored and the amateurs will be frustrated. It’s also blocked when one person dominates, is arrogant, or doesn’t think anything can be learned from the conversation.

7. Familiarity

One pickup player told the sociologist Jason Jimerson that “you gotta know how to play with them”— group flow is more likely to happen when players know the performance styles of their teammates and opponents. By studying many different work teams, psychologists have found that familiarity increases productivity and decision-making effectiveness… But if group members are too similar, flow becomes less likely because the group interaction is no longer challenging. If everyone functions identically and shares the same habits of communicating, nothing new and unexpected will ever emerge because group members don’t need to pay close attention to what the others are doing, and they don’t continually have to update their understanding of what is going on… Organizations should have mechanisms in place to smooth these natural transitions in the life span of creative groups.

8. Communication

Group flow requires constant communication. Everyone hates to go to useless meetings; but the kind of communication that leads to group flow often doesn’t happen in the conference room. Instead, it’s more likely to happen in freewheeling, spontaneous conversations in the hallway, or in social settings after work or at lunch.

9. Moving It Forward

Group flow flourishes when people follow the first rule of improvisational acting: “Yes, and . . .” Listen closely to what’s being said; accept it fully; and then extend and build on it.

10. The Potential for Failure

During rehearsal, jazz ensembles rarely experience flow; it seems to require an audience and the accompanying risk of real, meaningful failure… There’s no creativity without failure, and there’s no group flow without the risk of failure. Since group flow is often what produces the most significant innovations, these two common research findings go hand in hand. There’s a way to rehearse and improve, even in the business world. Psychological studies of expertise have shown that in every walk of life, from arts and science to business, the highest performers are those who engage in deliberate practice— as they’re doing a task, they’re constantly thinking about how they could be doing it better, and looking for lessons that they can use next time. The key is to treat every activity as a rehearsal for the next time…

And what should you make sure to take away from all of this?

The paradox of improvisation is that it can happen only when there are rules and the players share tacit understandings, but with too many rules or too much cohesion, the potential for innovation is lost. The key question facing groups that have to innovate is finding just the right amount of structure to support improvisation, but not so much structure that it smothers creativity. Jazz and improv theater have important messages for all groups because they’re unique in how successfully they balance all these tensions. These types of ensemble art forms embrace the tensions that drive group genius.

Join 45K+ readers. Get a free weekly update via email here.

Related posts:

Creative Teams – What 7 elements do they all share?