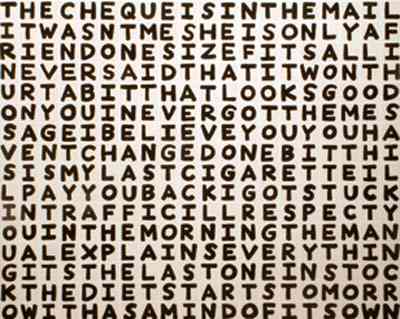

Why do lies often stick better than the truth?

.

Discussing misinformation while trying to correct it often strengthens the inaccurate belief.

Via The Chronicle of Higher Education:

“There is a risk that repeating an association can make it stronger in memory,” says Ullrich K.H. Ecker, another author, in an e-mail. “Saying that ‘it’s incorrect that the flu vaccine has major side effects’ repeats and hence potentially strengthens the link between ‘vaccine’ and ‘side effects’ even though it negates it,” notes Ecker, an assistant professor of psychology at Western Australia. His research and that of others has demonstrated this. Much smarter, he says, is to stick to the alternative, talking about the safety of the vaccine.

So what’s the best way to correct an inaccurate belief? Make sure the new explanation fits the same facts so it can replace the prior one. The right explanation needs to “click” as nicely as the wrong one did:

You need to find an alternate explanation that fits the same basic facts, says another report author, Colleen M. Seifert, a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. Misinformation persists when “you don’t have an alternative account that works as well as does the wrong one,” she explains by e-mail.

Join 25K+ readers. Get a free weekly update via email here.

Related posts:

What kind of photo can make you believe a pack of lies?

How does the human mind handle conflicts of interest?

Who cheats more: Americans, Israelis, Italians or the Chinese? Politicians or Wall Street bankers?