Does networking make you more creative?

.

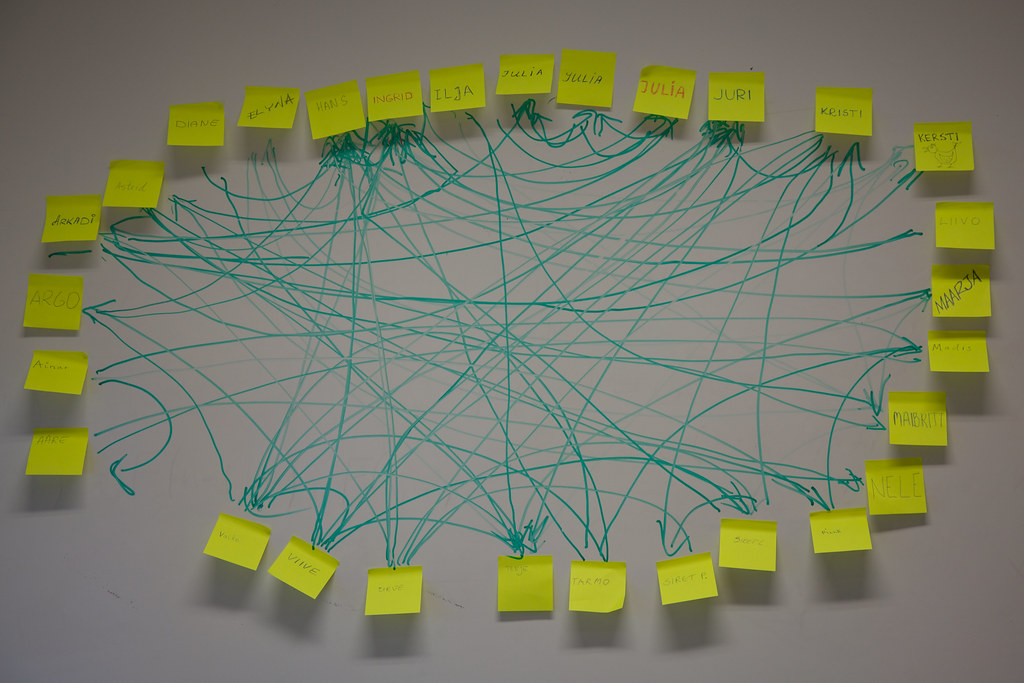

“…businesspeople with entropic networks full of weak ties were three times more innovative than people with small networks of close friends…”

Via Imagine: How Creativity Works:

Ruef then analyzed each of these entrepreneurs using an elaborate metric of innovation. He measured the number of patents they’d applied for and kept track of all their trademarks. He rated the originality of their products and gave them bonus points if they’d “entered an unexploited niche” or pioneered a new marketing method. He then compared these innovation rankings to the structure of each entrepreneur’s social network. The results were astonishing: businesspeople with entropic networks full of weak ties were three times more innovative than people with small networks of close friends. Instead of getting stuck in the rut of conformity— thinking the same tired thoughts as everyone else— they were able to invent profitable new concepts.

There is something unsettling about Ruef’s data. We think of entrepreneurs, after all, as creative individuals. If someone has a brilliant idea for a new company, we assume that he or she is inherently more creative than the rest of us. This is why we idolize people like Bill Gates and Richard Branson and Oprah Winfrey. But Ruef’s analysis suggests that this focus on the singular misses the real story of innovation. The most creative ideas, it turns out, don’t occur when we’re alone. Rather, they emerge from our social circles, from collections of acquaintances who inspire novel thoughts. Sometimes the most important people in life are the people we barely know.

And via Little Bets: How Breakthrough Ideas Emerge from Small Discoveries:

Gehry’s experience with Rauschenberg illustrates the remaining pattern of action that Dyer and Gregersen found distinguished the innovators from the noninnovators that we haven’t yet covered: innovators routinely networked with people who came from different backgrounds. It’s a way to challenge one’s assumptions and gain broader insight. For Dyer’s and Gregersen’s research pool of creative executives, the people who were sources of inspiration might include artists, academics, scientists, politicians, or adventurers.

Indeed, Dyer’s and Gregersen’s finding mirrors a preponderance of evidence that indicates that diversity, be it of perspectives, experiences, or backgrounds, fuels creativity. We see this pattern at the individual, organizational, and societal level. Professor Keith Sawyer of Washington University summarized the topic well in his book Group Genius. Meanwhile, Frans Johansson’s book, The Medici Effect, builds on major pillars of psychology research to demonstrate how diverse teams are more likely to be innovative. University of California Berkeley Professor AnnaLee Saxnian and author Richard Florida have produced compelling analyses about how cities and regions with diverse workforces (from a functional standpoint) and frequent interpersonal interactions are more innovative.

Join over 195,000 readers. Get a free weekly update via email here.

Related posts:

How To Stop Being Lazy And Get More Done – 5 Expert Tips

How To Get People To Like You: 7 Ways From An FBI Behavior Expert

New Harvard Research Reveals A Fun Way To Be More Successful