A Special Forces Officer Teaches You 5 Secrets To Overcoming Adversity

.

Life can be really difficult sometimes. We all deal with it. But how do top performers overcome challenges? And what can we learn from them? I figured I’d call an expert.

Who knows about overcoming adversity? Special Forces.

So I called Mike Kenny. Mike’s a Special Forces Lieutenant Colonel with 22 years of service under his belt. For most of his career he was an 18 Alpha (Special Forces Officer) and is currently the Special Operations Forces liaison to the School of Advanced Military Studies.

Most of what you may think you know about Special Forces is wrong. You might be imagining summer movies and gun battles. But a lot of what they deal with isn’t all that much different from some of the challenges you face.

SEALs and Rangers specialize in “direct action” and “special reconnaissance.” Meanwhile, Special Forces is focused on “foreign internal defense” and “unconventional warfare.” That means preventing or assisting an insurgency. So, plain and simple, SF guys need a lot of people skills.

They’re good behind the gun, no doubt, but they spend a lot of their time working with people — and usually people who don’t speak their language and don’t share a common culture. Which means they face a lot of problems that you can’t just shoot or blow up.

Here’s what you can learn from Special Forces training about overcoming adversity.

1) Prepare, Prepare, Prepare

We often wait until the hurricane hits us to think about how we’re going to cope with it. Special Forces, on the other hand, is very big on preparing.

Via Masters of Chaos: The Secret History of the Special Forces:

The Special Forces are not a rapid deployment force; the secret of their success is intensive preparation. The men studied the area they were assigned as thoroughly as any Ph.D. student. They sucked up every available open-source and classified assessment of the demographics, tribal clans, local politics, religious leaders and schisms, history, terrain, infrastructure, road maps, power grids, water supplies, crops, and local economy. They planned, debated, and rehearsed both combat and follow-on operations.

Many of the benefits that come from preparation are obvious. Nobody thinks preparing is bad. But Mike pointed out something that isn’t so readily apparent.

Not only does preparation get all your ducks in a row but prep changes your attitude. You’re more confident and this creates an upward spiral that improves performance. Here’s Mike:

Something that people underestimate is that preparedness is not only that you’re hardening and conditioning your body, but there’s a powerful mental aspect. Physically, you know you’re prepared. You and your mind are going, “I’m ready for this. This is what they said their standard was, and I know I can do that. I know I’m at this level so that whatever they throw at me I know I am adequately conditioned.”

Research shows this feeling of control neutralizes stress and builds courage.

When you do blood tests on soldiers during a challenging task, what do you find? The level of stress hormones in their bodies doesn’t match the difficulty of the task, it matches their perception of the difficulty.

Via Maximum Brainpower: Challenging the Brain for Health and Wisdom:

What mattered was how closely the anticipated challenge matched the soldiers’ actual capabilities. We took blood samples from the four groups to see how the experience affected each group’s stress hormones… The soldiers who never knew the actual length of the march were asked at the end to estimate its length. The levels of stress hormones in their blood corresponded to the length they thought it was, not the length it actually was.

And what’s the best way to prepare? Make your training as close to the real thing as possible. Here’s Mike:

In Army parlance they say, “train like you fight.” Don’t screw around and say, “Okay, when it’s for real then we’ll really ramp up.” No, you need to do that now. You need to train as hard and as realistic as possible, because this notion that when it’s for real and the stakes are high, that’s when we’ll really turn it on and rise to the occasion… that’s not what happens. You will not rise to the occasion. You will sink to the lowest level of your training. It’s the truth.

(For more on how Special Forces and other elites make themselves fearless, click here.)

So preparation is pretty straightforward. But Special Forces is also big on something you probably never expected to hear from a military unit…

2) Creativity Isn’t Nice — It’s Essential

When we think about the military we think following orders, not creativity. But that changes when you’re talking about Special Forces.

A small independent unit can’t always rely on a division of tanks backing them up. They’ll have many problems they need to solve quickly, in the field, with little or no support. So resourcefulness is vital.

Via Chosen Soldier: The Making of a Special Forces Warrior:

The Special Forces are looking for more than someone who is tough and smart and plays well with others. They are looking for adaptability and flexibility, men who can look at a given task and come up with any number of ways to solve it. Someone with good entrepreneurial skills is a good candidate for Special Forces, since the work of the Green Berets often involves calculated risk and creative thinking. If one solution to a problem fails, they have to immediately come up with another way to accomplish the mission.

The army calls this type of creativity “disciplined initiative.” It’s not wild and crazy risk-taking, but it definitely looks outside the conventional for how to solve difficult problems. Here’s Mike:

…in SF, and now the Army at large, you hear constantly we need agile and adaptive leaders and thinkers, critical and creative thinkers. Special Operations has always valued it, and I think out of necessity, because with smaller units you’ve got to be creative and adaptive, because you don’t always have all the resources at your disposal. What they want is a guy that can think on his feet and think somewhat unconstrained. To me, there’s always this tension between the cowboy that does crazy stuff for the sake of doing crazy stuff and those that can exercise what in Army mission command they call “disciplined initiative.” That means, “We want you to exercise initiative, but the discipline lies in keeping it within mission parameters to achieve the commander’s intent.”

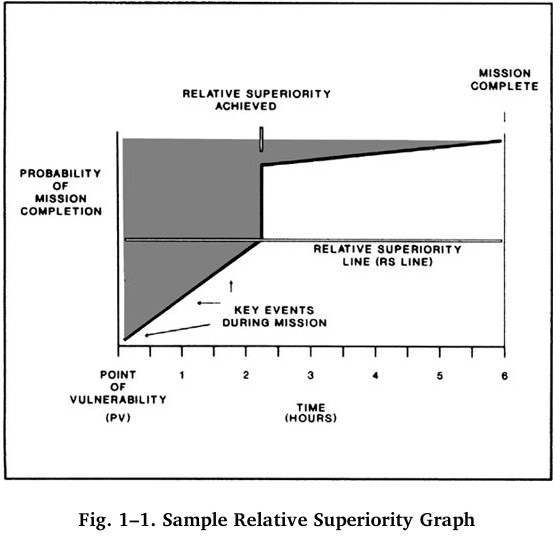

But how does creativity allow Davids like small Special Forces units to overcome Goliaths like bigger groups of enemy soldiers? The key is what’s called “relative superiority.”

Objective superiority is more soldiers, more guns, more planes. Relative superiority is tactical, like using surprise or timing or a well-planned ambush. This is why creativity is so critical to SF.

Via Spec Ops: Case Studies in Special Operations Warfare: Theory and Practice:

Relative superiority is a concept crucial to the theory of special operations. Simply stated, relative superiority is a condition that exists when an attacking force, generally smaller, gains a decisive advantage over a larger or well-defended enemy… An inherent weakness in special forces is their lack of firepower relative to a large conventional force. Consequently when they lose relative superiority, they lose the initiative, and the stronger form of warfare generally prevails. The key to a special operations mission is to gain relative superiority early in the engagement. The longer an engagement continues, the more likely the outcome will be affected by the will of the enemy, chance, and uncertainty, the factors that comprise the frictions of war.

(For more on the four principles that will lead you to breakthrough creativity, click here.)

So SF is not just gung-ho testosterone. And that means they know how to deal with people.

3) Cooperate and Negotiate

Author Dick Couch, who followed a class of Special Forces cadets through training put it bluntly: Special Forces needs to know how to shoot people and make friends with people.

That separates them from most of the other special operations groups like SEALs and Rangers who are more focused on “direct action” missions.

Via Chosen Soldier: The Making of a Special Forces Warrior:

Since the work often involves working as a team or in a cross-cultural environment, the Special Forces are looking for candidates who have good interpersonal skills— men who are open to listening and working with other people and foreign communities. More crudely put, it may come down to whether a man is more comfortable in shooting people or trying to make friends with them. Some soldiers are very proficient in a tactical situation and very comfortable behind the gun, but they don’t really want to make the effort to communicate with someone different from themselves.

And this isn’t the kind of negotiation that involves the barrel of a gun. SF needs to empathize just like FBI hostage negotiators. Plain and simple, they need to get along with people and cut a good deal. Here’s Mike:

The negotiating comes in having humility. We want to cultivate a relationship, and do what’s mutually beneficial. So we can’t come in and say, “Okay, this is what you’re going to do for me.” The diplomacy lies in convincing these guys that a relationship is going to be mutually beneficial. That’s one. Number two, we want to add value. We want to bring certain things to the table and find some common ground, because a lot of people are going to think, “You’re just going to tell me what to do” or “I’m not going to be your pawn, I’m not going to be your patsy.” We’re sensitive to what it is that they want. And we’ll help them get it, provided it’s not something that runs counter to what it is the US government needs to achieve.

(For FBI behavioral expert strategies on getting people to like you, click here.)

Collaboration and negotiation are so critical because SF works with and through others. And what are they doing most of the time with partners? Teaching.

4) Be A Teacher

Want to truly be the best? Want to be an expert? It’s one thing to be able to do but it’s another level to be able to do and teach it to others. That’s when you really understand something.

A fundamental concept to all SF soldiers is that they are teachers. Here’s Mike:

We’ll tell guys up front, “Hey, your primary job is as a teacher, as an instructor.” Our bread and butter mission is unconventional warfare. The Surgical Strike portion of our portfolio is important no doubt, but the Special Warfare part of that portfolio is what people need to understand. It implies that we’re going to be working through proxies. That means I have to be able to teach. I need to be able to convey information. I need to be able to influence diplomatically, because these are partners. They’re not subordinates where I say, “You do this.” You’ve got to win them over. You’ve got to be able to convince them, so if you can’t instruct, if you can’t work through a proxy, through another party, and you’ve got to do everything unilaterally yourself, as an SF guy I don’t want to say you’re worthless, but you’re not that valuable.

And your ability to teach well is always limited by how much you actually know. So Special Forces are always looking to improve themselves. Here’s Mike:

To be a professional you have to be a lifelong learner. You’re always getting better. You’re always trying to get better. A buddy of mine was saying, “Good, better, best. Never let it rest until your good is better and your better is best.”

How good do they need to be? A good example is the “pile test.” To qualify as an 18 Bravo (a Special Forces weapons expert) they dump a huge pile of weapon parts in front of you. You have a limited amount of time to assemble them all into nine guns.

Via Masters of Chaos: The Secret History of the Special Forces:

As a weapons sergeant his job was to know everything about all the small arms and crew-served weapons in use around the world: Soviet-made systems, black-market weapons, customized weapons. He had to know how to use them, train on them, fix them, clean them, dismantle them, and disable them. Part of the final exam for his course was the “pile test,” which required assembling a massive jumble of weapons parts into nine guns. Randy could do it in forty-five minutes.

(For more on the science of being the best at anything, click here.)

This is a lot of stuff SF is working at. So how do they get it all done?

5) Be Motivated — And Then Make A Plan

Want to be in SF because it’s “cool”?

You’ll never make it. The guys who pass are the ones who have a deep-seated desire. The vetting is too punishing for anyone who isn’t 100% committed. Here’s Mike:

I saw so many guys showing up at Ranger School and SFAS on day one and you could tell they really weren’t switched on. Then there were guys that were laughing and really really cavalier. A lot of times those guys didn’t make it, because they really weren’t serious about being there. The only thing that’s going to sustain you then is not, “I thought it would be cool” or “I want all my friends to be impressed” or whatever lame reason you have for putting yourself through that. The thing that’s going to keep you motivated is when you really internally want it, when you have that desire.

Of course, whenever someone talks about motivation they always say, “you have to want it.” But what’s that really mean to SF?

For them, motivation needs to translate into a plan for readiness. It’s not all talk. If your motivation doesn’t turn into a blueprint for how to handle things then it’s just cheerleading.

What conditioning will you need to pass SF training? The guys who make it are motivated to find out ahead of time. Then they do diagnostic runs to see where they’re at and what it will take for them to get there.

The motivation becomes a plan. Here’s Mike:

Develop that plan and break it down into steps, so, using the SFAS model as an example, you can say, “Okay, I’ve got to do 12 miles with 70 pounds. Okay, great, I’m going to do it,” and then you realize, “Oh my God, I can’t do this.” So you need to break it down and build. Start out, doing a six-miler with 35 pounds. Then when your conditioning goes up, extend the mileage, increase the weight, and then at the end of a six-month process or so you should be at that goal.

(For more on how you can motivate yourself, click here.)

Let’s round this up and learn the last critical factor for overcoming adversity like Special Forces.

Sum Up

Here’s what we can learn from Special Forces Officer Mike Kenny:

- Prepare, Prepare, Prepare

- Creativity Isn’t Just Nice — It’s Essential

- Cooperate and Negotiate

- Be A Teacher

- Be Motivated — And Then Make A Plan

A lot of this sounds very serious. But in the preparation for every post about the various special operations units I’ve talked to, one thing comes up again and again that isn’t so serious: the power of humor.

Ranger Joe Asher said it:

I said, “You know what? If I can laugh once a day, every day I’m in Ranger School, I’ll make it through.”

Navy SEAL James Waters said it:

You’ve got to have fun and be able to laugh; laugh at yourself and laugh at what you’re doing. My best friend and I laughed our way through BUD/S.

The formal research backs them up. And in researching Special Forces, sure enough, I heard it again.

Via Chosen Soldier: The Making of a Special Forces Warrior:

This training is serious business, and it will demand your best effort to be successful, but every day, try to smile at least once. A little humor will help you to get through this, and it might even help some when it starts to hurt.

Work hard. Be diligent. But make sure to laugh along the way.

Join over 180,000 readers. Get a free weekly update via email here.

Related posts:

A Navy SEAL Explains 8 Secrets To Grit And Resilience

New Harvard Research Reveals A Fun Way To Be More Successful