Faith In Humanity: 10 Studies To Restore Your Hope For The Future

.

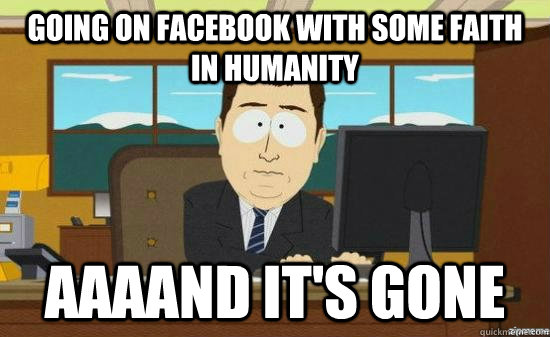

Reading a lot about the science of human behavior can make you cynical, sometimes deservedly so, but cynical nonetheless.

On this blog I try to be accurate and useful and, as I have posted, research shows there is great power in optimism and hope.

So I want to take a second to step back from brass tacks and take a look at some studies that can renew a faith in humanity.

The world is not always fair. The bad are not always punished and the good do not always prevail.

But there are plenty of reasons, scientifically tested, to have hope and be positive about the future.

1) You Bounce Back Better From Tougher Problems

From a study by Harvard happiness expert Daniel Gilbert, author of Stumbling on Happiness:

People rationalize divorces, demotions, and diseases, but not slow elevators and uninspired burgundies. The paradoxical consequence is that people may sometimes recover more quickly from truly distressing experiences than from slightly distressing ones (Aronson & Mills, 1958; Gerard & Mathewson, 1966; Zimbardo, 1966)…

2) Regret Is Not That Scary

We anticipate regret will be much more painful than it actually is. Studies show we consistently overestimate how regret affects us.

Another one from Stumbling on Happiness author Daniel Gilbert.

…margins of loss can have an impact on emotional experience, and our studies merely suggest that however powerful that impact is, it is not as powerful as people anticipate.

3) “What Does Not Kill You Makes You Stronger” Is Often True

Individuals who went through the most awful events came out stronger than those who did not face any adversity.

Via Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being:

In a month, 1,700 people reported at least one of these awful events, and they took our well-being tests as well. To our surprise, individuals who’d experienced one awful event had more intense strengths (and therefore higher well-being) than individuals who had none. Individuals who’d been through two awful events were stronger than individuals who had one, and individuals who had three— raped, tortured, and held captive for example— were stronger than those who had two.

4) Reverse PTSD Exists: Sometimes Terrible Events Make Us Better People

Tragedy not only can make us stronger, it can also make us better human beings.

Thanks to this study, today we can say for certain, not just anecdotally, that great suffering or trauma can actually lead to great positive change across a wide range of experiences. After the March 11, 2004, train bombings in Madrid, for example, psychologists found many residents experienced positive psychological growth. So too do the majority of women diagnosed with breast cancer. What kind of positive growth? Increases in spirituality, compassion for others, openness, and even, eventually, overall life satisfaction. After trauma, people also report enhanced personal strength and self-confidence, as well as a heightened appreciation for, and a greater intimacy in, their social relationships.

5) Rarely In Life Are You Limited By Your Genes

How often does natural talent limit what you are capable of?

In ~95% of cases, it doesn’t.

Via Mindset: The New Psychology of Success:

Benjamin Bloom, an eminent educational researcher, studied 120 outstanding achievers. They were concert pianists, sculptors, Olympic swimmers, world-class tennis players, mathematicians, and research neurologists. Most were not that remarkable as children and didn’t show clear talent before their training began in earnest… Bloom concludes, “After forty years of intensive research on school learning in the United States as well as abroad, my major conclusion is: What any person in the world can learn, almost all persons can learn, if provided with the appropriate prior and current conditions of learning.” He’s not counting the 2 to 3 percent of children who have severe impairments, and he’s not counting the top 1 to 2 percent of children at the other extreme… He is counting everybody else.

6) You Don’t Need To Win The Lottery To Be Happy

Very happy people don’t experience more happy events than less happy people.

Via 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology: Shattering Widespread Misconceptions about Human Behavior:

Ed Diener and Martin Seligman screened over 200 undergraduates for levels of happiness, and compared the upper 10% (the “extremely happy”) with the middle and bottom 10%. Extremely happy students experienced no greater number of objectively positive life events, like doing well on exams or hot dates, than did the other two groups (Diener & Seligman, 2002).

7) Helping Others Helps You

Undergrads who wrote letters of encouragement to “at-risk” middleschoolers advising them to persevere and that intelligence “is not a finite endowment but rather an expandable capacity” became, themselves, happier and better in school for months afterward.

Truth is, there were no middleschoolers. Just writing the letters achieved these results.

Via Situations Matter: Understanding How Context Transforms Your World:

Did these letters help the middle school students bounce back from adversity? It’s impossible to say — the letters were never delivered. But the mere experience of writing them had a lasting impact on the college students themselves. Months later, the letter writers were still reporting greater enjoyment of school than were other Stanford undergrads. Their grade point averages were higher, too, by a full third of a point on a four-point scale.

8) “Both hope and despair are self-fulfilling prophecies.”

Bloodwork performed on soldiers in challenging situations shows the body is stressed by the perceived, not actual, difficulty of circumstances.

Via Maximum Brainpower: Challenging the Brain for Health and Wisdom:

…the brain does not want the body to expend its resources unless we have a reasonable chance of success. Our physical strength is not accessible to us if the brain does not believe in the outcome, because the worst possible thing for humans to do is to expend all of our resources and fail. If we do not believe we can make it, we will not get the resources we need to make it. The moment we believe, the gates are opened, and a flood of energy is unleashed. Both hope and despair are self-fulfilling prophecies.

9) Trusting Too Much Is Better Than Trusting Too Little

People were asked how much they trust others on a scale of 1 to 10. Income peaked at those who responded with the number 8.

Those with the highest levels of trust had incomes 7% lower than the 8′s. Research shows they are more likely to be taken advantage of.

Those with the lowest levels of trust had an income 14.5% lower than 8′s. That loss is the equivalent of not going to college. They missed many opportunities by not trusting.

10) Sometimes, Empathy Beats Objectivity

From my interview with Wharton Professor Adam Grant, author of Give and Take: A Revolutionary Approach to Success:

There is a great study of radiologists by Turner and colleagues showing that when radiologists just saw a photo of the patient whose x-ray they were about to scan, they empathized more with the person, seeing that person as more of a human being as opposed to just an x-ray. As a result, they wrote longer reports, and they had greater diagnostic accuracy, significantly.

And One More:

11) The Most Powerful Goals Aren’t About Being Perfect; They’re About Getting Better

Get-better goals increase motivation, make tasks more interesting and replenish energy. This effect even carries over to subsequent tasks.

Via Nine Things Successful People Do Differently:

Get-better goals, on the other hand, are practically bulletproof. When we think about what we are doing in terms of learning and mastering, accepting that we may make some mistakes along the way, we stay motivated despite the setbacks that might occur… Research shows that a focus on getting-better also enhances the experience of working; we naturally find what we do more interesting and enjoyable when we think about it in terms of progress, rather than perfection.

And getting better is what this blog is all about.

Join 45K+ readers. Get a free weekly update via email here

Related posts:

What 10 things should you do every day to improve your life?

What do people regret the most before they die?

What five things can make sure you never stop growing and learning?