Genius And Insanity: Do You Need To Be Crazy To Be The Best?

.

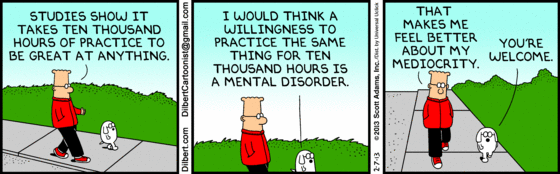

Research says experts practice for 10,000 hours. That’s a lot of hours. A crazy amount of hours, one might say.

I’ve posted a lot about “deliberate practice” and the work habits of geniuses. They’re relentless.

Via Daily Rituals: How Artists Work

“Sooner or later,” Pritchett writes, “the great men turn out to be all alike. They never stop working. They never lose a minute. It is very depressing.”

Here’s the question:

Is that just something that obsessed, crazy people do? Does this prove the often-theorized connection between genius and insanity?

We assume 10,000 hours of practice means passion or dedication. How often does it just mean stone-cold obsessed?

Brilliant, Famous — And Utterly Obsessed

Steve Jobs? Brilliant and obsessed.

Via America’s Obsessives: The Compulsive Energy That Built a Nation:

He insisted that the walls all be painted white. “No white was too white for Steve,” stated Coleman. Jobs would also don white gloves to do frequent dust checks. Whenever he spotted a few specks on either a machine or on the floor, which he was determined to keep clean enough to eat off, Coleman had to arrange for an instant scrubbing.

That was in Apple’s factory — not someplace consumers would ever see.

Dying of cancer didn’t make a difference. He demanded the oxygen mask the doctors put on him be redesigned.

Via America’s Obsessives: The Compulsive Energy That Built a Nation:

When the sedated cancer patient was lying in his hospital bed, he once ripped off his oxygen mask, railing that he hated its design. Much to the surprise of his doctors, Jobs then ordered them to begin work on five different options for a new mask.

But there was no doubt this obsessiveness made him great.

Via America’s Obsessives: The Compulsive Energy That Built a Nation:

Apple’s stupendous growth in the first decade of the twenty-first century occurred precisely because Steve Jobs was both an obsessive like Ray Lane and a narcissist like Larry Ellison; he was a two-for-one. While obsessive innovators also possess the grandiosity and self-absorption characteristic of narcissists, they are driven primarily by their particular obsessions and compulsions; and it is precisely this connection between unremitting internal pressures and extraordinary external achievements that has received surprisingly little attention.

Thomas Jefferson read fifteen hours a day in order to complete college in 2 years. He kept track of every single cent he ever spent in his life.

Via America’s Obsessives: The Compulsive Energy That Built a Nation:

And in his account books, which he maintained for nearly sixty years, he kept track of every cent he ever spent. “Mr. Jefferson,” the overseer at Monticello once observed, “was very particular in the transaction of all his business. He kept an account of everything. Nothing was too small for him to keep an account of it.”

Alfred Kinsey, groundbreaking sex researcher, recorded sex histories on almost 8000 people, put together the world’s largest collection of sex books and, deciding that the Dewey Decimal system was inadequate, created his own method of classification.

Via America’s Obsessives: The Compulsive Energy That Built a Nation:

…he also amassed the world’s largest collection of sex books. The Dewey Decimal Classification System, this iconoclast decided, would not do, so he devised his own. Kinsey placed brown tape at the bottom of the spines upon which he wrote in white ink one of his thirty designations— say, FM for modern fiction and AN for anthropology. He also stashed away in the institute every erotic artifact and factoid he could lay his hands on, including ceramic art from Peru, bathroom graffiti, and some 5,200 penis measurements. This chase consumed him right up until his death. “It is a shame,” he noted in 1956, after gathering his final two sex histories— Numbers 7984 and 7985—“ there comes a time that you have to work up data and publish it instead of continuing the gathering. Frankly, I very much enjoy the gathering.”

I’ve posted about Paul Erdos, the “all-roads-lead-to-Rome” of the mathematics world, being obsessive at the extreme, wandering the world in search of new challenges with numbers.

Genius and insanity? Yup.

Via The Man Who Loved Only Numbers: The Story of Paul Erdos and the Search for Mathematical Truth:

He lived out of a shabby suitcase and a drab orange plastic bag from Centrum Aruhaz (“Central Warehouse”), a large department store in Budapest. In a never-ending search for good mathematical problems and fresh mathematical talent, Erdos crisscrossed four continents at a frenzied pace, moving from one university or research center to the next. His modus operandi was to show up on the doorstep of a fellow mathematician, declare, “My brain is open,” work with his host for a day or two, until he was bored or his host was run down, and then move on to another home.

Baseball legend Ted Williams didn’t just obsessively swing a bat, he also zealously amassed data to perfect his skills, long before “Moneyball.”

Via America’s Obsessives: The Compulsive Energy That Built a Nation:

…he began gathering info on opposing pitchers, which he kept in a little black book. Like a dogged investigative journalist, he would dig and dig and dig. To get the full scoop on a given pitcher’s habits, he would quiz not only any veteran who would listen to his flood of questions but also umpires… His fieldwork also included a visit to the physics lab at Cambridge’s Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he learned about the trajectory of baseballs upon impact. “Some people called it monomania,” Richard Ben Cramer observed in his landmark 1986 Esquire article, “What Do You Think of Ted Williams Now?” of the thoroughness with which Williams studied hitting, “but with Ted it was serial (multimania?) in eager furtherance of everything he loved.”

(To learn how to make people like you, click here.)

Beyond “A Good Work Ethic”

Here’s where we stop saying “genius and insanity” loosely. There are connections between creativity and mental disorders.

More specifically, obsessively thinking about things is connected to depression — but it’s also correlated with creativity:

Because rumination may allow an idea to stay in one’s conscious longer and indecision may result in more time on a given task, it was expected that these two cognitive processes may predict creativity.

This rumination/perseverence connection can be a double edged sword for creative people:

“Successful writers are like prizefighters who keep on getting hit but won’t go down,” Andreasen says. “They’ll stick with it until it’s right. And that seems to be what the mood disorders help with.” While Andreasen acknowledges the terrible burden of mental illness— she quotes Robert Lowell on depression not being a “gift of the Muse” and describes his reliance on lithium to escape the pain— she argues that, at least in its milder forms, the disorder benefits many artists due to the perseverance it makes possible. “Unfortunately, this type of thinking is often inseparable from the suffering,” Andreasen says. “If you’re at the cutting edge, then you’re going to bleed.”

Obsessive people can be hell to be around, genius or not. What did Ted Williams’ second wife, model Lee Howard, say at their divorce hearing?

Via America’s Obsessives: The Compulsive Energy That Built a Nation:

When asked by the judge at her divorce hearing whether there was any chance of reconciling with her husband, a startled Howard responded, “Are you kidding?”

(To learn the secret to being happier and more successful, click here.)

The Dark Side

Harvard’s Howard Gardner studied a number of creative geniuses and found that to reach those heights requires enormous sacrifice in other areas of life — what amounted to a Faustian bargain.

Einstein lived in self-imposed isolation, Freud had an ascetic existence and Picasso became a selfish monster.

And Gardner’s study reveals that without these personal sacrifices they would not have been capable of their great achievements.

If hours alone determine genius then it is inevitable that reaching the greatest heights will be indistinguishable from pathological obsession.

In general, the creators were so caught up in the pursuit of their work mission that they sacrificed all, especially the possibility of a rounded personal existence. The nature of this arrangement differs: In some cases (Freud, Eliot, Gandhi), it involves the decision to undertake an ascetic existence; in some cases, it involves a self-imposed isolation from other individuals (Einstein, Graham); in Picasso’s case, as a consequence of a bargain that was rejected, it involves an outrageous exploitation of other individuals; and in the case of Stravinsky, it involves a constant combative relationship with others, even at the cost of fairness. What pervades these unusual arrangements is the conviction that unless this bargain has been compulsively adhered to, the talent may be compromised or even irretrievably lost. And, indeed, at times when the bargain is relaxed, there may well be negative consequences for the individual’s creative output.

(To learn how Navy SEALs develop grit and never give up, click here.)

Back To Reality

Personally, you probably don’t need to worry about the line between genius and insanity.

You’re not going to get tied up in a Faustian bargain with your work, and let everything fall by the wayside to perfect your art.

But you can still learn from the crazies.

They did what they loved. They spent the time, probably enjoying the process much more than yet another hour of Netflix, and they became great.

Opportunity is missed by most people because it is dressed in overalls and looks like work. – Thomas Edison

If you want a healthy amount of what they had, what should you do next?

Start educating yourself. Which of the below is your weak spot?

Click, read and improve:

Join over 195,000 readers. Get a free weekly update via email here.

Related posts:

How To Stop Being Lazy And Get More Done – 5 Expert Tips

How To Get People To Like You: 7 Ways From An FBI Behavior Expert

New Harvard Research Reveals A Fun Way To Be More Successful