Dan Ariely Explains When Your Irrational Behavior Is A Good Thing

.

Dan Ariely teaches psychology and behavioral economics at Duke University and is the bestselling author of three books I love:

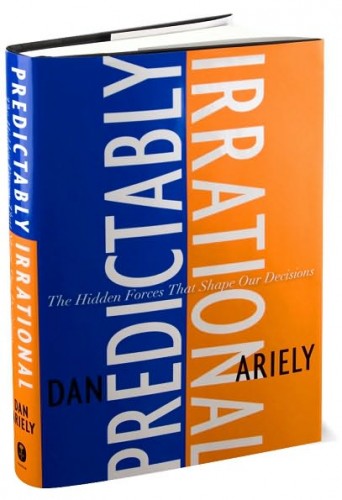

- Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions

- The Upside of Irrationality: The Unexpected Benefits of Defying Logic

- The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty: How We Lie to Everyone—Especially Ourselves

Here’s one of his TED talks:

Dan has an online course called “A Beginner’s Guide to Irrational Behavior“. You can check it out here.

He and I spoke about the ups and downs of irrationality, how to make better decisions, and overcoming procrastination.

My conversation with Dan was over 45 minutes, so for brevity’s sake I’m only going to post edited highlights here.

Subscribers to my free weekly newsletter get access to extended interviews.

Join here.

———————————————

Irrationality Can Be A Good Thing

Eric:

Can you talk about the Lego study, the IKEA effect and people’s investment in things?

Dan:

So this is a great example of something that is irrational but wonderful. And what we’ve basically found is that the moment that you invest something of yourself into something, you start overvaluing it. My personal experience started with IKEA furniture which is the reason that we call it the IKEA effect. But what happened was I’m not particularly good in assembling things and it took me a long time. I made all kinds of mistakes. But I found out that when I finished assembling this truly mediocre piece of furniture, I was actually incredibly proud of it and I kept moving it with me from city-to-city as I would keep on moving, while the objective quality of it did not support that.

And I started wondering whether my love of it was due to my investment of time and energy. And we’ve done all kinds of experiments on this. We’ve done experiments with people doing origami and building Legos. And what’s interesting is when people build origami, okay, every origami’s a little different so maybe people cannot get attached to it. But when you build Legos based on instructions, there are no differences between the Legos you build and somebody else builds. But even with those provisions, people still attach more to the kind of Lego that they created.

I think the most extreme example of this is kids. So I haven’t done this experiment, but this is a question I ask many people. I say imagine I would come to you. I go to people with kids, and I would come to you and I would say would you sell me your kids? How much money would you charge me if I wanted to buy your kids and take all your memories and association and so on and I promise to give them a good home. And as long as these are not teenagers, people say lots of money. They can’t see their lives without the kids. And I say imagine a different place. Imagine that you don’t have kids. You went to a park and you met these two kids and you played with them for a few hours and they were wonderful little kids just like your kids right now. And after a few hours, you were ready to say goodbye, but before you said goodbye, the parents said you know, by the way, they are for sale. Are you interested? How much would you pay for those kids? And most people at that time basically realize that they wouldn’t pay much for these kids.

And I think this is because kids are an ideal example of the IKEA effect. We love our kids. I have two kids; I think they’re the most adorable kids in the world. We just went skiing and I couldn’t believe it, anybody else wanted to do anything on the mountain besides watching my kids ski. How could they find anything else more adorable? If you want, I’ll send you the video. But the realization I think is we love them so much because they’re our kids. We think that IKEA furniture comes with better instructions. Kids really come with no instructions. Very tough to deal with, difficult, complex, but incredibly involving and time consuming and I think the love that comes out of it is an example of the effect of a tremendous investment.

What happens when we try to overcome our irrationality?

Eric:

So in terms of trying to use your research practically, what do you think most people do wrong when it comes to trying to be more rational or trying to overcome their biases? What mistakes do most people make?

Dan:

When they try? I think most people don’t try. There’s some really beautiful research by Wilson and Schooler showing that when people decide about buying jams and you get them to think very carefully about it, they actually get jams they don’t like. So sometimes when people try to be more rational, what they end up doing is they just think more cognitively and they think less about what they like and they think more about what’s the right thing to do. So in the Wilson and Schooler example, you give people jams and jams are not a rational product. It’s about what you enjoy and what you don’t enjoy. But you give people the choice between jams and you tell them to think hard about it. What they end up doing is they buy jams that they don’t end up liking. They’re basically trying to do the right thing by a computation, and it ends up not being the thing that they enjoy.

Are Creative People More Dishonest?

Eric:

Can you talk a little about the connection between creativity and dishonesty?

Dan:

Yes. So think about what we find about dishonesty. What we find is it’s a struggle between two forces. You want to think of yourself as an honest, wonderful person on one hand and you want to gain from dishonesty on the other hand. And the way you can do it is to tell yourself a story about why this is actually okay. So ask yourself who can tell better stories? It turns out more creative people can tell better stories, so that’s actually what we find. We find it when we measure students that are more creative, they cheat more. We find that when we use priming to increase creativity, we also increase dishonesty. And when we went to an advertising agency, we also found that the people in the advertising agency who were in more creative job titles also had more flexibility.

What Books Do You Recommend?

Dan:

Take the “Outside Perspective”

Eric:

If somebody said to you “What’s a tip I can use tomorrow?” — what would your piece of advice be, gleaning from your research?

Dan:

If I had to give advice across many aspects of life, I would ask people to take what’s called “the outside perspective.” And the outside perspective is easily thought about: “What would you do if you made the recommendation for another person?” And I find that often when we’re recommending something to another person, we don’t think about our current state and we don’t think about our current emotions. We actually think a bit more distant from the decision and often make the better decision because of that.

———————————————

Subscribers to my free weekly newsletter get access to extended interviews. Join here.

Related posts:

What 10 things should you do every day to improve your life?

What do people regret the most before they die?

What five things can make sure you never stop growing and learning?