Effective Executive: 5 insights from the #1 management book

.

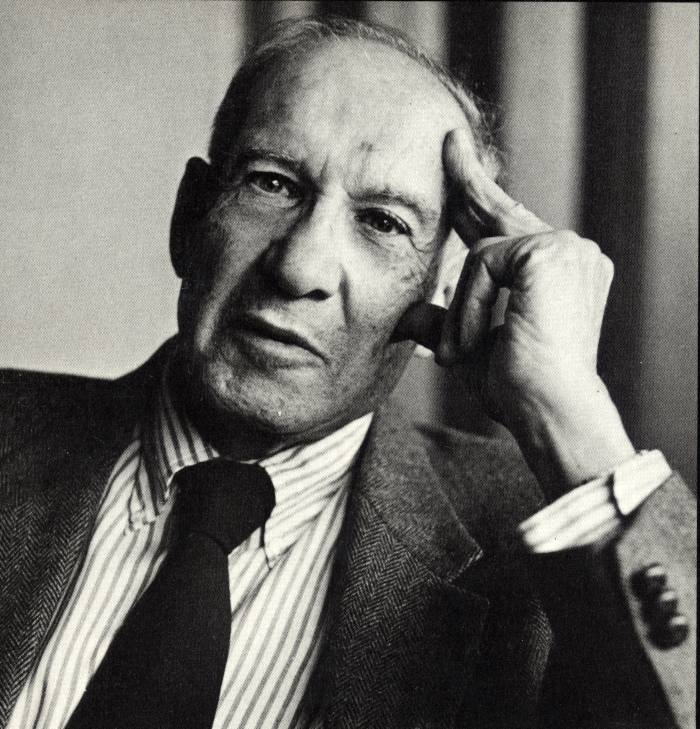

Pete Drucker‘s book The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done is one of my most frequent recommendations.

Everyone can get something from it because it’s not about the minutiae of business, it’s about organizing your life so you can accomplish the things that are important.

Drucker is probably the most influential writer on the subject of management. Why? One of the reasons is that he understood that the most important part of management is knowing yourself.

What are the book’s most critical lessons?

1. “Effective executives know where their time goes. They work systematically at managing the little of their time that can be brought under their control.”

Record how you spend your time. Cut the things that steal it. Then consolidate your time into chunks big enough to accomplish good work.

Via The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done:

Effective executives, in my observation, do not start with their tasks. They start with their time. And they do not start out with planning. They start by finding out where their time actually goes. Then they attempt to manage their time and to cut back unproductive demands on their time. Finally they consolidate their “discretionary” time into the largest possible continuing units. This three-step process: recording time, managing time, and consolidating time…

2. “Effective executives focus on outward contribution. They gear their efforts to results rather than to work. They start out with the question, “What results are expected of me?” rather than with the work to be done, let alone with its techniques and tools.”

Don’t focus on the work in front of you, focus on results. If you’re just doing what comes in, you’re on the treadmill, not making a difference.

Via The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done:

If the executive lets the flow of events determine what he does, what he works on, and what he takes seriously, he will fritter himself away “operating.” He may be an excellent man. But he is certain to waste his knowledge and ability and to throw away what little effectiveness he might have achieved. What the executive needs are criteria which enable him to work on the truly important, that is, on contributions and results, even though the criteria are not found in the flow of events.

3. “Effective executives build on strengths—their own strengths, the strengths of their superiors, colleagues, and subordinates; and on the strengths in the situation, that is, on what they can do. They do not build on weakness.”

Judge people by what they’re good at. If you want people who are competent at everything you’ll end up with a team of mediocrities.

Via The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done:

The task is not to breed generalists. It is to enable the specialist to make himself and his specialty effective. This means that he must think through who is to use his output and what the user needs to know and to understand to be able to make productive the fragment the specialist produces… We can so structure as to make the strength relevant. A good tax accountant in private practice might be greatly hampered by his inability to get along with people. But in an organization such a man can be set up in an office of his own and shielded from direct contact with other people. In an organization one can make his strength effective and his weakness irrelevant.

Want to get ahead? You must do this for your boss as well. Stop bitching about what they’re bad at and do the work necessary to allow them to focus on what they are good at.

Via The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done:

Conversely, there is nothing quite as conducive to success, as a successful and rapidly promoted superior… The effective executive, therefore, asks: “What can my boss do really well?” “What has he done really well?” “What does he need to know to use his strength?” “What does he need to get from me to perform?” He does not worry too much over what the boss cannot do… Subordinates typically want to “reform” the boss. The able senior civil servant is inclined to see himself as the tutor to the newly appointed political head of his agency. He tries to get his boss to overcome his limitations. The effective ones ask instead: “What can the new boss do?” And if the answer is: “He is good at relationships with Congress, the White House, and the public,” then the civil servant works at making it possible for his minister to use these abilities.

Same goes for yourself. Do not turn yourself into a mediocre generalist. Delegate what you’re not good at and spend your time on what you are.

4. “Effective executives concentrate on the few major areas where superior performance will produce outstanding results. They force themselves to set priorities and stay with their priority decisions. They know that they have no choice but to do first things first—and second things not at all. The alternative is to get nothing done.”

Getting things done is not enough. You must get the right things done. What is most important? Focus on that.

Via The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done:

To be effective is the job of the executive. “To effect” and “to execute” are, after all, near-synonyms. Whether he works in a business or in a hospital, in a government agency or in a labor union, in a university or in the army, the executive is, first of all, expected to get the right things done. And this is simply that he is expected to be effective… All in all, the effective executive tries to be himself; he does not pretend to be someone else. He looks at his own performance and at his own results and tries to discern a pattern. “What are the things,” he asks, “that I seem to be able to do with relative ease, while they come rather hard to other people?”

5. “Effective executives, finally, make effective decisions. They know that this is, above all, a matter of system—of the right steps in the right sequence. They know that an effective decision is always a judgment based on “dissenting opinions” rather than on “consensus on the facts.” And they know that to make many decisions fast means to make the wrong decisions. What is needed are few, but fundamental, decisions.”

The best decision makers don’t make many decisions. They focus on the ones that are important and the ones only they can solve. How can they do this?

Most situations are generic and have a standard solution. Once you understand this and know the standard solutions you can cut through the easy problems and focus on the few unique management problems that really require effort.

Via The Effective Executive: The Definitive Guide to Getting the Right Things Done:

The effective executive does not need to make many decisions. Because he solves generic situations through a rule and policy, he can handle most events as cases under the rule; that is, by adaptation. “A country with many laws is a country of incompetent lawyers,” says an old legal proverb. It is a country which attempts to solve every problem as a unique phenomenon, rather than as a special case under general rules of law. Similarly, an executive who makes many decisions is both lazy and ineffectual. The decision-maker also always tests for signs that something atypical, something unusual, is happening; he always asks: “Does the explanation explain the observed events and does it explain all of them?; he always writes out what the solution is expected to make happen—make automobile accidents disappear, for instance—and then tests regularly to see if this really happens; and finally, he goes back and thinks the problem through again when he sees something atypical, when he finds phenomena his explanation does not really explain, or when the course of events deviates, even in details, from his expectations.

Join over 205,000 readers. Get a free weekly update via email here.

Related posts:

How To Stop Being Lazy And Get More Done – 5 Expert Tips

How To Get People To Like You: 7 Ways From An FBI Behavior Expert

New Harvard Research Reveals A Fun Way To Be More Successful